Works Cited: Gou Tanabe's Visions of Lovecraft (Complete)

Artist Gou Tanabe continues to breathe new life into the Cthulhu Mythos with his lovingly detailed manga adaptations.

Introduction |

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Shadow Over Innsmouth |

In a 2019 press conference, Junji Ito—the reigning king of horror manga—was asked about his Eisner Award-winning adaptation of Frankenstein and whether he was interested in reimagining any other classic works. His response began as many fans hoped it would before taking an unexpected turn:

I love H.P. Lovecraft and really admire him. It would be great to adapt him as a serialized manga, but I actually saw Gou Tanabe create a great adaption of H.P. Lovecraft's stories. Afterwards, I ended up not doing it because I thought I wouldn't be as good as Gou's version.

Fans had long suspected that Lovecraft was a major influence on Ito, so it seemed inevitable that Ito would eventually adapt one of his stories. However, no one foresaw him deferring to another artist, one who had both beaten him to the punch and humbled him in the process.

| |

|

This was startlingly high praise for a mangaka whose name had only recently become known in the West. With that said, Gou Tanabe's first works in English made waves upon their release. Several months before Ito's remarks, Dark Horse released Tanabe's ambitious adaptation of At the Mountains of Madness, which one reviewer described as "so spot-on, it makes every other attempt to draw Lovecraft (of which there have been no shortage over the years) seem ill-advised" (Lehoczky). Two years prior, Tanabe made his English debut with the Lovecraft-focused collection The Hound and Other Stories. Both works earned Eisner award nominations for "Best Adaptation from Another Medium".

In this piece, I will be examining several ways in which Gou Tanabe adapts H.P. Lovecraft's stories into the comics medium, some more successful than others. Tanabe's meticulously detailed artwork hews as closely to the original descriptions as is possible in black-and-white manga, giving shape to Lovecraft's most notoriously surreal creations and demonstrating why his name is still synonymous with cosmic horror to this day. The mangaka occasionally takes a more liberal approach with narrative structure and tone, though, resulting in some themes becoming lost in translation. Nonetheless, these Lovecraft adaptations are among the finest ever published, and these minor oversights hardly affect the visceral impact of Tanabe's art.

* * *

A quick note before progressing: of the pieces discussed in this article, The Hound and Other Stories, At the Mountains of Madness, The Shadow Over Innsmouth, and The Call of Cthulhu are currently the only ones officially translated into English. The other featured works—The Haunter of the Dark and The Colour Out of Space—are only available in Japanese and French, and as a result, I will be referencing unofficial English scanlations for now.

Terrifying Vistas

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Shadow Over Innsmouth 93-94 |

Though H.P. Lovecraft is best known for his creatures, who are monstrous not just for their sheer size or bizarre physiology but for their remote origins and insidious influences on our planet, the spaces that they inhabit are just as horrifying. A desolate, decaying fishing village and a sepulchrous undersea city are treated with the same gravity as any cosmic entity. Lovecraft's protagonists can hardly believe their eyes when they glimpse these "terrifying vistas of reality" ("The Call of Cthulhu"), incapable of understanding the forces at work. The horror comes from the paradoxes inherent to these spaces—here, dimensions clash and binaries fall to pieces as the surreal becomes real.

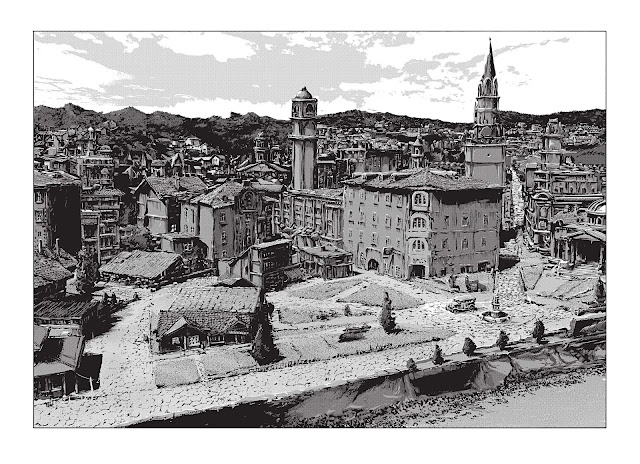

"The Shadow Over Innsmouth" is one such story in which the eldritch and familiar collide in a deeply unsettling fashion. Its primary antagonists are 1) a cult that worships an ancient fish god, and 2) urban decay, and in early chapters, the narrator can't decide which perturbs him more. He describes Innsmouth's decrepit slums as if surveying a mass grave:

"Collapsing huddles of gambrel roofs formed a jagged and fantastic skyline, above which rose the ghoulish, decapitated steeple of an ancient church. Some houses along Main Street were tenanted, but most were tightly boarded up. Down unpaved side streets I saw the black, gaping windows of deserted hovels, many of which leaned at perilous and incredible angles through the sinking of part of the foundations. Those windows stared so spectrally that it took courage to turn eastward toward the waterfront. Certainly, the terror of a deserted house swells in geometrical rather than arithmetical progression as houses multiply to form a city of stark desolation."

(Lovecraft, "The Shadow Over Innsmouth")

The empty edifices are personified as maimed cadavers with ghastly, leering eyes. In a town abandoned by industry, all that remains of the once-bustling seaport is a hollowed-out husk that harbors an inhuman evil just beneath the surface. Gou Tanabe's recently released adaptation captures this haunting, oppressive stillness in painstaking detail (remember to read right to left):

| |

|

The buildings in the ruined square are battered and broken, choked with vines—a patchwork of mouldering boards and disintegrating bricks. A place so devoid of (human) life stirs up a primal dread that cannot be ignored. It is a fitting prelude to the horrors that await once night falls and the town's remaining inhabitants awake.

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Shadow Over Innsmouth |

Tanabe expertly frames this scene with the narrator gazing in frightful awe at the Order's headquarters, knowing full well that the doors will soon burst open and flood the streets below with shambling, fish-eyed creatures. The only way out is through, and thus the protagonist must either proceed across the sea of rotting tiles or dive into one of the forsaken houses.

If the challenge posed by The Shadow Over Innsmouth was transforming a coastal New England village into a harrowing labyrinth, then what of Lovecraft's more alien locales? These are frequently described in purposefully vague yet increasingly overwrought adjectives, simulating the narrators' inability to comprehend what lies before them. Take the formerly (and subsequently) undersea city of R'lyeh in "The Call of Cthulhu", whose immense scale and warped proportions infamously defy human conception. The story's narrator discovers the collected writings of one H.A. Wilcox, who had begun to dream "with terrible vividness [a] damp Cyclopean city of slimy green stone—whose geometry, he oddly said, was all wrong" (Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu" Ch. II). R'lyeh had resurfaced after untold millennia, sending both physical and psychic shockwaves around the world, and it's not long before a storm-tossed ship stumbles across the "the nightmare corpse-city"(Ch. III). The narrator paraphrases from the Second Mate's journal, remarking that

"Without knowing what futurism is like, Johansen achieved something very close to it when he spoke of the city; for instead of describing any definite structure or building, he dwells only on broad impressions of vast angles and stone surfaces—surfaces too great to belong to any thing right or proper for this earth [...]"

(Ch. III)

This immediately raises a question: if Johansen cannot adequately describe what he is seeing, and even the narrator himself struggles to make sense of this madman's ramblings, how can an illustrator render these impossible sights in a way that conveys their impossibility? The task of adapting such willfully obtuse prose is a daunting and thankless one to be sure. Tanabe chooses to reflect the city's surreal construction with a disorienting and disturbingly organic approach that recalls the colliding shapes of Picasso, and Duchamp:

|

| Tanabe, The Call of Cthulhu |

Aside from scattered carvings in what appears to be some sort of cuneiform, the scene is almost entirely incomprehensible. One's focus is drawn in every direction before inevitably slipping away into oblivion. Even the heights of the explorers themselves seems variable when juxtaposed with these clashing axes of carved stone.

One of my favorite moments in the ensuing escape sequence involves a small detail that epitomizes the city's maddening complexity. Johansen is temporarily "swallowed up by an angle of masonry which shouldn’t have been there; an angle which was acute, but behaved as if it were obtuse"(Ch. III), and the implication that one can get lost in the intersection between two planes is a brilliant little brain teaser. Tanabe deftly solves this paradox by quoting the Penrose Triangle (again, remember to read right to left):

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Call of Cthulhu 218 |

While this may not exactly convey the disparity between the angle's appearance and its reality as seen from Johansen's point of view, illustrating this sequence from an observer's perspective gives Tanabe an opportunity to show Johansen somehow falling into a stray angle. To achieve this in a two dimensional medium as opposed to, say, an immersive 3D environment, is a stroke of genius.

Innsmouth and R'lyeh sit at opposite extremes: the former was once a quaint New England fishing village before it was slowly consumed by the terrible Deep Ones, while the latter was a charnel city constructed eons ago by extraterrestrial (and likely extradimensional) beings that has become a psycho-spiritual beacon for a legion of human cultists. One is a victim of a monstrous corrupting force while the other is the corrupting force, and Gou Tanabe's illustrations underscore the most alienating qualities of each. Whether drawing ruined city squares or cyclopean obelisks, Tanabe brings readers face-to-face with the eerie and the impossible, fully realizing Lovecraft's conceit of architecture as antagonist.

Cosmic Chromaticism

|

| Tanabe, Gou. H.P. Lovecraft's At the Mountains of Madness Volume 2 |

One of the most subtle details in Lovecraft's imagery is his use of color (and you will hopefully forgive me if I deliberately avoid any discussion of Lovecraft's opinions on race, genetics, etc.). His narrators must contend with the suffocating darkness of the ocean depths as well as brilliant hues that shine with extradimensional luminosity, finding them just as confounding as any alien city.

This poses an interesting challenge to a mangaka like Gou Tanabe, whose illustrations are primarily black-and-white. He works within this limitation to create stark contrasts for extreme environments—see "The Temple" and "At the Mountains of Madness"—and while the omission of color is noticeable in some cases, Tanabe manages to illustrate "The Colour Out of Space" in a way that somehow imbues an otherworldly luminosity with texture—a feat for any artist in this medium.

We begin with "The Temple", a relatively early Lovecraft story that takes place almost entirely onboard the German submarine U-29. Its narrator, Lieutenant Commander Karl Heinrich, slowly falls victim to "the vastness, darkness, remoteness, antiquity, and mystery of the oceanic abysses" (Lovecraft, "The Temple") after discovering a fragment of an ancient carving. The tale's psychological horror builds on the basic human fear of the dark, and its narrative revelations are, appropriately, only made possible by the sub's searchlight. After all, and there's not much that Heinrich can describe about what he can't see.

Gou Tanabe's adaptation, on the other hand, fully submerses the reader in the jet-black Atlantic waters. The darkness here is so pure, so all-encompassing, that the vessel's feeble lights are barely capable of illuminating the nearby terrain, and Tanabe frequently depicts the submarine surrounded by crushing gloom:

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Hound and Other Stories |

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Hound and Other Stories, 63 |

Tanabe achieves an appropriately subtle yet chilling effect by barely outlining any of the city's defining features. The soft, eerie glow issuing forth from each doorway lights the surrounding stonework just enough to imply tiers of dwellings in the massive undersea ziggurat. Who or what is still tending the altar? Are they still human, or were they ever human to begin with? Neither the original story nor Tanabe's adaptation answers these questions, after spending so much of the story literally in the dark, even the slightest bit of inexplicable light is cause for alarm.

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's At the Mountains of Madness Volume 1 |

As the protagonist, Dyer, approaches by plane, Tanabe emphasizes how even the sky begins to change over the mountains. The clouds hang low and heavy opposite the setting sun, and as the aircraft prepares to cross over into the unknown, heaven and earth mark the border:

| |

|

The black-and-white artwork has its shortcomings, though. Actual colors must be left to the reader's imagination, such as the omnipresent green of the aforementioned city of R'lyeh. Lovecraft writes of "green stone" covered by "green ooze" and, hidden within, a "gelatinous green immensity"("The Call of Cthulhu", Ch. III) from beyond time and space—a pattern clearly emerges. However, like most manga, Tanabe's take on "The Call of Cthulhu" is set in a greyscale world that, despite the superb shading, cannot quite elicit the same revolting response that green slime typically receives, especially when Tanabe rarely mentions the color during the hapless explorers' short, madness-inducing stint on the island.

Nonetheless, Tanabe excels in spite of these limitations in his his adaptation of "The Colour of Space". In this slow burn of a tale, a mysterious meteorite crashes onto a New England farm. Scientists take samples from its core and discover a substance of unclassifiable color and properties. Over half a century after Lovecraft published the story in 1927, Terry Pratchett would achieve a similar effect with the creation of octarine, the color of magic which was described as both an Ur-color "of which all the lesser colours are merely partial and wishy-washy reflections" and "a sort of greenish-purple". Lovecraft, however, offers no such hints or explanations as to the nature of his titular creation, going so far as to say that "it was only by analogy that they called it colour at all." The only other clues that Lovecraft provides are vague notions of "shining bands" and "luminosity" (Lovecraft, "The Colour Out of Space), and thus, Tanabe has free reign to illustrate the meteorite's undefinable hue as he pleases.

Tanabe accomplishes this with fluid, amorphous whorls of white and grey, preserving the purity of Lovecraft's vision with a paradoxical lack of color. It would, of course, be impossible for an illustrator to actually create a new, never-before-seen color outside of absurd branding efforts by major corporations (see Minion Yellow and Vantablack), so forcing readers to imagine the color for themselves is the perfect solution to this insurmountable problem.

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Colour Out of Space 33 |

As the story progresses and the meteorite's contents begins to transform the nearby flora, and farmers note "that the queer colour of that skunk-cabbage had been very like one of the anomalous bands of light shewn by the meteor fragment in the college spectroscope". The fact that Tanabe's version of this "color" is more of a texture allows him to visually represent its insidious spread with a similar "haunting familiarity" (Lovecraft, "The Colour Out of Space), an instantly identifiable match for what the scientists had discovered months before:

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Colour Out of Space 88 |

The region quickly becomes overrun with the mysterious color, which infects the surrounding landscape with its unearthly glow. The well, the trees, the house, and eventually the air itself become saturated until the color seems to come alive with ghostly light. All this is deftly illustrated with swirls of white and grey that still manage to contrast with the surrounding characters and backgrounds. The solution is so elegant that it makes me wonder why several other adaptations, such as this animation and the recent Nicholas Cage film, choose to represent the titular color as some sort of pinkish purple.

Morbid Palimpsests

| |

|

As mentioned above, Lovecraft set many of his most famous stories along the Eastern Seaboard, primarily New England. Alien horrors are brought home to normal, God-fearing Americans, and readers can undoubtedly empathize with Lovecraft's protagonists when they too are faced with horrors beyond comprehension.

To heighten this sense of nightmarish realism, Lovecraft also heavily relies on frame narratives in which protagonists—clear stand-ins for readers—uncover eldritch truths throughout the story, eventually succumbing to some sort of terrible consequence. If you will allow me to dramatically oversimplify what I view as the typical Lovecraft experience, imagine a mix of the old aphorisms "the devil is in the details" and "curiosity killed the cat".

Of Tanabe's Lovecraft adaptations, his Shadow Over Innsmouth is perhaps the most complete for how it faithfully maintains the original frame narrative, which opens with narrator Robert Olmstead pledging to reveal the truth of the titular Massachusetts town despite the federal government's attempts erase Innsmouth from history. Olmstead traces his lineage to this doomed fishing hamlet, and it was he who witnessed the return of an otherworldly force that, in a sense, had never left in the first place. He hints at "drastic measures" and "a terrible step which lies ahead" (Lovecraft, "The Shadow Over Innsmouth); then, in the conclusion, he references the suicide of his uncle Douglas, who shot himself after making a similar "ancestral journey". Olmstead's admittance that he "bought an automatic and almost took the step" clarifies his implication from the opening, which makes one wonder why Lovecraft was so purposefully vague to begin with.

Tanabe brings this revelation forward in his prologue while omitting the details about Robert's uncle, instead leaving the reader on a tense cliffhanger:

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Shadow Over Innsmouth 24 |

The panel transitions lend additional gravity to the prologue's final sentence, which had always passed me by whenever I read the original Lovecraft tale. Furthermore, the story's twist is hidden in plain sight. The awful secret that drove Douglas to suicide and nearly caused Robert to do the same is hinted at this transition point, albeit in a way that most will only notice on a second reading.

Then, at the very end of the adaptation, Tanabe deftly reframes Robert's dream of his dead grandmother by presenting the most important information through the Eliza Orne herself. Lovecraft's tendency to 'tell' rather than 'show' leads to climactic moments that ultimately feel like summaries. His version of the dream is a prime example of this, as Robert describes how his grandmother "had gone to a spot her dead son had learned about, and had leaped to a realm whose wonders—destined for him as well—he had spurned with a smoking pistol" (Lovecraft, "The Shadow Over Innsmouth"). The line feels much more eerie when presented to Robert (and the reader) by the dream manifestation of Eliza Orne, who leads him towards the truth that Douglas had tried to avoid:

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Shadow Over Innsmouth 417 |

This choice makes Robert's first-person narration feel much more immediate: he is no longer just paraphrasing his grandmother, but literally following in her footsteps, as his uncle was supposed to years before. The addition of the final line—"Can you imagine how it broke a mother's heart?"—reinforces Robert's connection to Innsmouth and, by extension, untold generations of ancestors before him.

Tanabe's adaptation of "The Call of Cthulhu" is similarly successful in foregrounding elements from the conclusion in order to give the story a sense of urgency. Lovecraft opens the original story with a brief and easily overlooked epigraph, which purports that the the first person narrative was "Found Among the Papers of the Late Francis Wayland Thurston, of Boston". Thurston drily recounts how he came into possession of his late uncle's various papers, among which are a "queer clay bas-relief" and a packet titled "CTHULHU CULT" ("The Call of Cthulhu"). The tale begins to take shape as Thurston follows up on three leads initially investigated by his uncle: a local sculptor plagued by nightmares, a police officer who bore witness to an unholy ritual deep in a Louisiana Bayou, and the sole survivor of a mysterious shipwreck. It's not until the conclusion that Thurston begins to fear for his own physical (as opposed to mental) well-being:

I have looked upon all that the universe has to hold of horror, and even the skies of spring and the flowers of summer must ever afterward be poison to me. But I do not think my life will be long. As my uncle went, as poor Johansen went, so I shall go. I know too much, and the cult still lives [...] A time will come—but I must not and cannot think! Let me pray that, if I do not survive this manuscript, my executors may put caution before audacity and see that it meets no other eye. (Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu")

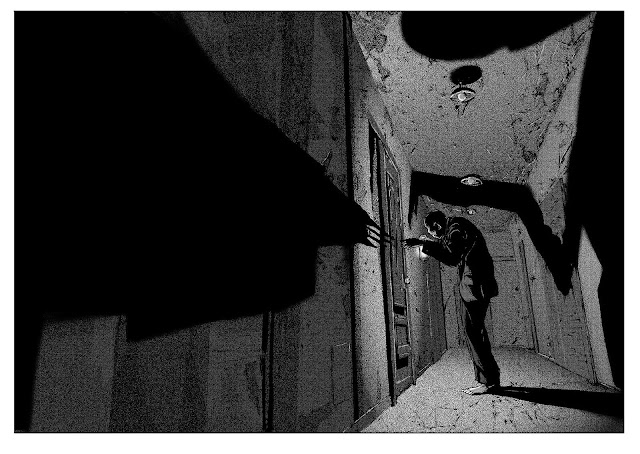

While the manga generally follows the same progression as the original tale, right down to the three-act structure, Tanabe adds an original prologue that makes immediately introduces Thurston's desperate attempt to write everything down before it's too late, thus making good on the epigraph's—and the frame narrative's—promise. Chased through the night by a pair of shadowy pursuers, Thurston runs home, locks the door, and begins writing this very story without a moment's hesitation:

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Call of Cthulhu |

Rather than idly musing about "the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents" and "the awesome grandeur of the cosmic cycle wherein our world and human race form transient incidents" like in the source material, Tanabe's version of Thurston writes those same words as the cultists close in on him, emphasizing that this manuscript is his "last will and testament" (Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Call of Cthulhu 281). Just as with The Shadow Over Innsmouth, Tanabe overhauls The Call of Cthulhu's frame narrative by emphasizing the narrator's impending doom from the very start.

In several other works, however, Tanabe's desire to immerse the reader in the storylines and imagery as soon as possible strips away some of the originals' complexity. His Haunter of the Dark faithfully begins with the mangled body of the late Robert Blake, who was allegedly "killed by lightning, or by some profound nervous shock derived from an electrical discharge." The exact circumstances are, of course, revealed over the course of the tale, but where Tanabe ever-so-slightly deviates from the original story is in telling the tale from Blake's point of view, as opposed to Lovecraft's relatively distant limited omniscient narrator who snidely doubts all supernatural explanations for the protagonist's demise from the very start. Tanabe only hints at this in his introduction as he lingers on Blake's pen, forever halted mid-sentence:

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Haunter of the Dark |

Lovecraft's narrator is far more critical in the opening paragraphs, going on to write that "among those, however, who have examined and correlated all this evidence, there remain several who cling to less rational and commonplace theories. They are inclined to take much of Blake’s diary at its face value" (Lovecraft, "The Haunter of the Dark"). By stripping away much of this ironic veneer, Tanabe embraces the "less rational" explanations for Blake's condition and welcomes the reader to do the same. After all, the manga version does what the story cannot: it clearly depicts the titular creature, thus making its existence an objective truth. Where Lovecraft maintains his poker face, Tanabe shows his hand.

But this does not mean that the original narration cannot coexist with this nameless, shapeless being. In Understanding Comics, author and artist Scott McCloud discusses the various types of word/image relationships that can be found throughout the medium, with one in particular that stands out as being unique: the "interdependent" mode, in which "words and pictures go hand in hand to convey an idea that neither could convey alone" (McCloud 155). He demonstrates comics' capacity for irony with the following examples:

The white lie of the first excerpt and the wry humor of the second show how text can contradict an image to yield a much more interesting story together than if they were presented separately. Thus, there it would be perfectly reasonable for Tanabe to illustrate an eldritch beast erupting from a church tower in the dead of night while also preserving the same ironic detachment of Lovecraft's narrator.

The only other remnant of this tone in the manga can be found in a newspaper article that Blake reads as as rumors of otherworldly forces begin to spread throughout the city:

| |

|

This is a step in the right direction with its characterization of the crowd's "whimsical" and "fanatical" speculations, but another issue soon presents itself. Lovecraft's narrator summarizes the report with a scathing critique of the the townsfolk, in a passage that is noticeably absent from the manga:

"The verdict, of course, was charlatanry. Somebody had played a joke on the superstitious hill-dwellers, or else some fanatic had striven to bolster up their fears for their own supposed good. Or perhaps some of the younger and more sophisticated dwellers had staged an elaborate hoax on the outside world. There was an amusing aftermath when the police sent an officer to verify the reports. Three men in succession found ways of evading the assignment, and the fourth went very reluctantly and returned very soon without adding to the account given by the reporters."

(Lovecraft, "The Haunter of the Dark")

One can almost imagine Lovecraft chuckling to himself as he insults these yokels, so easily duped by a few scraps of cloth and a foul smell, knowing full well that the reader yearns to be just as credulous as those "superstitious hill-dwellers". In the manga version, readers have no choice but to believe.

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Haunter of the Dark |

Tanabe uses a similar sort of narrative streamlining in his adaptation of At the Mountains of Madness, though this choice has more controversial and wide-ranging implications. The original At the Mountains of Madness is written from the perspective of Professor Dyer, a geologist from the fictional Miskatonic University who, along with a bevy of fellow academics and explorers, embarks upon a perilous journey deep into the Antarctic continent. Dyer's intent from the first line of the Lovecraft story is to reveal why he is opposed to further exploration of the region and to tell all after a period of careful silence: "I am forced into speech because men of science have refused to follow my advice without knowing why" (Lovecraft, At the Mountains of Madness Ch. I) The story thus takes on the tone of an impassioned plea contextualized with long stretches of personal testimony and occasional transcripts from the doomed sub-expedition led by the brash biologist Dr. Lake. Its first three chapters recapitulate the facts previously revealed to the public after Dyer's return to States, but beginning with the fourth, the beleaguered professor attempts to fully explain what he and his student Danforth discovered and "break through all reticences at last—even about that ultimate nameless thing beyond the mountains of madness" (Ch. III).

| |

|

"Still another time have I come to a place where it is very difficult to proceed. I ought to be hardened by this stage; but there are some experiences and intimations which scar too deeply to permit of healing, and leave only such an added sensitiveness that memory reinspires all the original horror." (Ch. XI)

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's At the Mountains of Madness Volume 2 324 |

It would be unfair to say that Tanabe neglects this plot point, as it is represented here clear as day. However, its relegation to the epilogue does sap some of its thematic potency. Instead of permeating the narration from the start and hanging over the reader like the "sinister, curling mist" in Lovecraft's novella (Ch. XI), Dyer's attempt to prevent further Antarctic exploration is only revealed to the reader at the chronologically "correct" point in time rather than the most rhetorically effective. This page goes so far as to openly acknowledge the frame narrative of the original by combining narration from the very first chapter of original with commentary from the conclusion:

"The coming Starkweather-Moore Expedition proposes to follow [our route] despite the warnings I have issued since our return from the Antarctic"

(Lovecraft, At the Mountains of Madness Ch. I)

"It is absolutely necessary, for the peace and safety of mankind, that some of earth’s dark, dead corners and unplumbed depths be let alone; lest sleeping abnormalities wake to resurgent life."

(Lovecraft, At the Mountains of Madness Ch. XII)

Conclusion - Who Knows the End?

Works Cited

Chik, Kalai. "Interview: Horror Manga Mastermind Junji Ito". Anime News Network. 17 Sept. 2019. https://www.animenewsnetwork.com/interview/2019-09-17/horror-manga-mastermind-junji-ito/.151216. Accessed 26 Dec. 2023.

"DARK HORSE COMICS 2018 EISNER NOMINEES ANNOUNCED!". Dark Horse Blog. 27 April 2018. https://www.darkhorse.com/Blog/2708/dark-horse-comics-2018-eisner-nominees-announced. Accessed 19 January 2024.

"DARK HORSE RECEIVES 13 EISNER AWARD NOMINATIONS". Dark Horse Blog. 4 June 2020. https://www.darkhorse.com/Blog/3176/dark-horse-receives-13-eisner-award-nominations. Accessed 19 January 2024.

DuChamp, Marcel. Nude Descending a Staircase (no. 2). The Cleveland Museum of Art, https://www.clevelandart.org/centennial/centennial-loans/marcel-duchamp-nude-descending-a-staircase-no.-2

Lehoczky, Etelka. "" NPR, 5 Dec. 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/12/05/784829291/at-the-mountains-of-madness-spheroid-space-monsters-are-just-like-us. Accessed 7 Jan. 2024.