Gou Tanabe's Visions of Lovecraft, Part 2: Terrifying Vistas

Gou Tanabe's landscapes are equal parts breathtaking and terrifying, capturing the horror in the mundane and the cosmic alike.

|

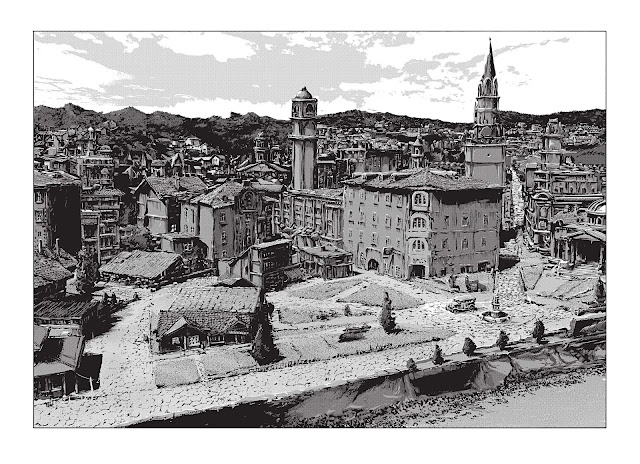

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Shadow Over Innsmouth 93-94 |

If you're just jumping on board—or need to refresh your memory—check out Part 1 here.

Though H.P. Lovecraft is best known for his creatures, who are monstrous not just for their sheer size or bizarre physiology but for their remote origins and insidious influences on our planet, the spaces that they inhabit are just as horrifying. A desolate, decaying fishing village and a sepulchrous undersea city are treated with the same gravity as any cosmic entity. Lovecraft's protagonists can hardly believe their eyes when they glimpse these "terrifying vistas of reality" ("The Call of Cthulhu"), incapable of understanding the forces at work. The horror comes from the paradoxes inherent to these spaces—here, dimensions clash and binaries fall to pieces as the surreal becomes real.

"The Shadow Over Innsmouth" is one such story in which the eldritch and familiar collide in a deeply unsettling fashion. Its primary antagonists are 1) a cult that worships an ancient fish god, and 2) urban decay, and in early chapters, the narrator can't decide which perturbs him more. He describes Innsmouth's decrepit slums as if surveying a mass grave:

"Collapsing huddles of gambrel roofs formed a jagged and fantastic skyline, above which rose the ghoulish, decapitated steeple of an ancient church. Some houses along Main Street were tenanted, but most were tightly boarded up. Down unpaved side streets I saw the black, gaping windows of deserted hovels, many of which leaned at perilous and incredible angles through the sinking of part of the foundations. Those windows stared so spectrally that it took courage to turn eastward toward the waterfront. Certainly, the terror of a deserted house swells in geometrical rather than arithmetical progression as houses multiply to form a city of stark desolation."

(Lovecraft, "The Shadow Over Innsmouth")

The empty edifices are personified as maimed cadavers with ghastly, leering eyes. In a town abandoned by industry, all that remains of the once-bustling seaport is a hollowed-out husk that harbors an inhuman evil just beneath the surface. Gou Tanabe's recently released adaptation captures this haunting, oppressive stillness in painstaking detail (remember to read right to left):

| |

|

The buildings in the ruined square are battered and broken, choked with vines—a patchwork of mouldering boards and disintegrating bricks. A place so devoid of (human) life stirs up a primal dread that cannot be ignored. It is a fitting prelude to the horrors that await once night falls and the town's remaining inhabitants awake.

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Shadow Over Innsmouth |

Tanabe expertly frames this scene with the narrator gazing in frightful awe at the Order's headquarters, knowing full well that the doors will soon burst open and flood the streets below with shambling, fish-eyed creatures. The only way out is through, and thus the protagonist must either proceed across the sea of rotting tiles or dive into one of the forsaken houses.

If the challenge posed by The Shadow Over Innsmouth was transforming a coastal New England village into a harrowing labyrinth, then what of Lovecraft's more alien locales? These are frequently described in purposefully vague yet increasingly overwrought adjectives, simulating the narrators' inability to comprehend what lies before them. Take the formerly (and subsequently) undersea city of R'lyeh in "The Call of Cthulhu", whose immense scale and warped proportions infamously defy human conception. The story's narrator discovers the collected writings of one H.A. Wilcox, who had begun to dream "with terrible vividness [a] damp Cyclopean city of slimy green stone—whose geometry, he oddly said, was all wrong" (Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu" Ch. II). R'lyeh had resurfaced after untold millennia, sending both physical and psychic shockwaves around the world, and it's not long before a storm-tossed ship stumbles across the "the nightmare corpse-city"(Ch. III). The narrator paraphrases from the Second Mate's journal, remarking that

"Without knowing what futurism is like, Johansen achieved something very close to it when he spoke of the city; for instead of describing any definite structure or building, he dwells only on broad impressions of vast angles and stone surfaces—surfaces too great to belong to any thing right or proper for this earth [...]"

(Ch. III)

This immediately raises a question: if Johansen cannot adequately describe what he is seeing, and even the narrator himself struggles to make sense of this madman's ramblings, how can an illustrator render these impossible sights in a way that conveys their impossibility? The task of adapting such willfully obtuse prose is a daunting and thankless one to be sure. Tanabe chooses to reflect the city's surreal construction with a disorienting and disturbingly organic approach that recalls the colliding shapes of Picasso, and Duchamp:

|

| Tanabe, The Call of Cthulhu |

Aside from scattered carvings in what appears to be some sort of cuneiform, the scene is almost entirely incomprehensible. One's focus is drawn in every direction before inevitably slipping away into oblivion. Even the heights of the explorers themselves seems variable when juxtaposed with these clashing axes of carved stone.

One of my favorite moments in the ensuing escape sequence involves a small detail that epitomizes the city's maddening complexity. Johansen is temporarily "swallowed up by an angle of masonry which shouldn’t have been there; an angle which was acute, but behaved as if it were obtuse"(Ch. III), and the implication that one can get lost in the intersection between two planes is a brilliant little brain teaser. Tanabe deftly solves this paradox by quoting the Penrose Triangle (again, remember to read right to left):

|

| Tanabe, H.P. Lovecraft's The Call of Cthulhu 218 |

While this may not exactly convey the disparity between the angle's appearance and its reality as seen from Johansen's point of view, illustrating this sequence from an observer's perspective gives Tanabe an opportunity to show Johansen somehow falling into a stray angle. To achieve this in a two dimensional medium as opposed to, say, an immersive 3D environment, is a stroke of genius.

Innsmouth and R'lyeh sit at opposite extremes: the former was once a quaint New England fishing village before it was slowly consumed by the terrible Deep Ones, while the latter was a charnel city constructed eons ago by extraterrestrial (and likely extradimensional) beings that has become a psycho-spiritual beacon for a legion of human cultists. One is a victim of a monstrous corrupting force while the other is the corrupting force, and Gou Tanabe's illustrations underscore the most alienating qualities of each. Whether drawing ruined city squares or cyclopean obelisks, Tanabe brings readers face-to-face with the eerie and the impossible, fully realizing Lovecraft's conceit of architecture as antagonist.

Works Cited

DuChamp, Marcel. Nude Descending a Staircase (no. 2). The Cleveland Museum of Art, https://www.clevelandart.org/centennial/centennial-loans/marcel-duchamp-nude-descending-a-staircase-no.-2

Lovecraft, H.P. "The Call of Cthulhu". The H.P. Lovecraft Archive, https://www.hplovecraft.com/writings/texts/fiction/cc.aspx.

Lovecraft, H.P. "The Shadow Over Innsmouth". The H.P. Lovecraft Archive, https://www.hplovecraft.com/writings/texts/fiction/soi.aspx.

Picasso, Pablo. Accordionist (L’accordéoniste). Gugenheim, https://www.guggenheim.org/artwork/3426.

Tanabe, Gou. H.P. Lovecraft's The Call of Cthulhu. Beam Comics, 2019.

Tanabe, Gou. H.P. Lovecraft's The Shadow Over Innsmouth. Dark Horse, 2023.

Weisstein, Eric W. "Penrose Triangle." From MathWorld--A Wolfram Web Resource. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/PenroseTriangle.html. Accessed 28 Dec 2023.